Chet Baker — Autumn Leaves

Нет других произведений.

Чесни «Чет» Генри Бейкер (англ. Chesney «Chet» Henry Вaker; род. 23 декабря 1929, Йейл, штат Оклахома — 13 мая 1988, Амстердам, Нидерланды) — американский джазовый трубач, руководитель ансамбля. В плеяде трубачей, выдвинувшихся в начальный период развития модерн-джаза, Бейкер занимает одно из ведущих мест. Является первым белым трубачом современного кул-стиля в сфере комбо-джаза. Ему принадлежит важная роль в экспериментах Джерри Маллигана с «бесклавишными» составами комбо, в которых отсутствие гармонической поддержки мелодических голосов партией фортепиано должно было восполняться за счет полифонизации фактуры и требовало развитого гармонического мышления от участников ансамбля. Данные опыты основывались на синтезе различных стилевых элементов модерн-джаза, свинга и современной академической камерной музыки, создали предпосылки для последующего расцвета кул-стиля и «третьего течения». Выступал также как певец, в вокале отличался мягкой лирической манерой исполнения, обладал необычно высоким, почти юношеским голосом.

В возрасте 11 лет приехал с семьей в Калифорнию. В школе обучался игре на трубе, затем начал выступать в духовых и танцевальных оркестрах. Службу в армии проходил в 3ападном Берлине как трубач военного оркестра (1946-48), после демобилизации продолжил музыкальное образование в колледже Эль-Камино (Лос-Анджелес), где изучал теорию музыки и гармонию. В 1949 получил приглашение в военный оркестр PRESIDIO ARMY BAND, с которым играл в Сан-Франциско до 1952. В этот период познакомился с музыкантами-боперами, участвовал в джем-сешнах.

В начале 1952 сотрудничал с Чарли Паркером и Видо Муссо, в конце того же года в Голливуде примкнул к Джерри Маллигену и вскоре стал знаменитостью как солист его квартета. В дальнейшем выступал преимущественно с собственным комбо (начиная с 1953), членом которого был также пианист Расс Фримен. Совершил несколько европейских турне в 1955-56. Возобновив сотрудничество с Маллигеном, успешно концертировал в составе его секстета в Париже (и как пианист). Аккомпанировал певице Катерине Валенте во время её гастролей в Баден-Бадене.

В 1959-60 находился в Италии, здесь из-за пристрастия к наркотикам перенёс психическое заболевание, был осуждён и в заключении прошёл курс лечения.

«Каждый раз я играю, как будто это последний раз. Уже много лет. Мне немного осталось, и очень важно, чтобы те, с кем я играю — кто бы это ни был, — видели, что я отдаю все, что у меня есть. И я от них жду того же. Мне нравится играть, я люблю играть. Наверное, я для этого и родился».

В 1964 вернулся из Европы в США, снова приобрел широкую известность, принимал участие в различных джазовых фестивалях (в Ньюпорте, Монтерее и др.). В разное время с Бэйкером играли музыканты из Франции, Бельгии, Голландии, ФРГ, Дании (в том числе Нильс-Хеннинг Эрстед-Педерсен, Вольфганг Лаккершмид и др.), среди его американских партнеров — пианисты «Дюк» Джордан, Эл Хэйг, Пол Блей и Дик Туордзик, саксофонисты Стэн Гетц, Ли Кониц, Арт Пеппер и Пол Дезмонд, гитарист Джим Холл, басисты Джимми Бонд, Чарли Хэйден и Рон Картер, барабанщики Питер Литмэн и «Бивер» Харрис.

Источник

Chet Baker

Чесни «Чет» Генри Бейкер (англ. Chesney «Chet» Henry Вaker; род. 23 декабря 1929, Йейл, штат Оклахома — 13 мая 1988, Амстердам, Нидерланды) — американский джазовый трубач, руководитель ансамбля. В плеяде трубачей, выдвинувшихся в начальный период развития модерн-джаза, Бейкер занимает одно из ведущих мест. Является первым белым трубачом современного кул-стиля в сфере комбо-джаза. Ему принадлежит важная роль в экспериментах Джерри Маллигана с «бесклавишными» составами комбо, в которых отсутствие гармонической поддержки мелодических голосов партией фортепиано должно было восполняться за счет полифонизации фактуры и требовало развитого гармонического мышления от участников ансамбля. Данные опыты основывались на синтезе различных стилевых элементов модерн-джаза, свинга и современной академической камерной музыки, создали предпосылки для последующего расцвета кул-стиля и «третьего течения». Выступал также как певец, в вокале отличался мягкой лирической манерой исполнения, обладал необычно высоким, почти юношеским голосом.

В возрасте 11 лет приехал с семьей в Калифорнию. В школе обучался игре на трубе, затем начал выступать в духовых и танцевальных оркестрах. Службу в армии проходил в 3ападном Берлине как трубач военного оркестра (1946-48), после демобилизации продолжил музыкальное образование в колледже Эль-Камино (Лос-Анджелес), где изучал теорию музыки и гармонию. В 1949 получил приглашение в военный оркестр PRESIDIO ARMY BAND, с которым играл в Сан-Франциско до 1952. В этот период познакомился с музыкантами-боперами, участвовал в джем-сешнах.

В начале 1952 сотрудничал с Чарли Паркером и Видо Муссо, в конце того же года в Голливуде примкнул к Джерри Маллигену и вскоре стал знаменитостью как солист его квартета. В дальнейшем выступал преимущественно с собственным комбо (начиная с 1953), членом которого был также пианист Расс Фримен. Совершил несколько европейских турне в 1955-56. Возобновив сотрудничество с Маллигеном, успешно концертировал в составе его секстета в Париже (и как пианист). Аккомпанировал певице Катерине Валенте во время её гастролей в Баден-Бадене.

В 1959-60 находился в Италии, здесь из-за пристрастия к наркотикам перенёс психическое заболевание, был осуждён и в заключении прошёл курс лечения.

«Каждый раз я играю, как будто это последний раз. Уже много лет. Мне немного осталось, и очень важно, чтобы те, с кем я играю — кто бы это ни был, — видели, что я отдаю все, что у меня есть. И я от них жду того же. Мне нравится играть, я люблю играть. Наверное, я для этого и родился».

В 1964 вернулся из Европы в США, снова приобрел широкую известность, принимал участие в различных джазовых фестивалях (в Ньюпорте, Монтерее и др.). В разное время с Бэйкером играли музыканты из Франции, Бельгии, Голландии, ФРГ, Дании (в том числе Нильс-Хеннинг Эрстед-Педерсен, Вольфганг Лаккершмид и др.), среди его американских партнеров — пианисты «Дюк» Джордан, Эл Хэйг, Пол Блей и Дик Туордзик, саксофонисты Стэн Гетц, Ли Кониц, Арт Пеппер и Пол Дезмонд, гитарист Джим Холл, басисты Джимми Бонд, Чарли Хэйден и Рон Картер, барабанщики Питер Литмэн и «Бивер» Харрис.

Источник

Chet Baker

Чесни «Чет» Генри Бейкер (англ. Chesney «Chet» Henry Вaker; род. 23 декабря 1929, Йейл, штат Оклахома — 13 мая 1988, Амстердам, Нидерланды) — американский джазовый трубач, руководитель ансамбля. В плеяде трубачей, выдвинувшихся в начальный период развития модерн-джаза, Бейкер занимает одно из ведущих мест. Является первым белым трубачом современного кул-стиля в сфере комбо-джаза. Ему принадлежит важная роль в экспериментах Джерри Маллигана с «бесклавишными» составами комбо, в которых отсутствие гармонической поддержки мелодических голосов партией фортепиано должно было восполняться за счет полифонизации фактуры и требовало развитого гармонического мышления от участников ансамбля. Данные опыты основывались на синтезе различных стилевых элементов модерн-джаза, свинга и современной академической камерной музыки, создали предпосылки для последующего расцвета кул-стиля и «третьего течения». Выступал также как певец, в вокале отличался мягкой лирической манерой исполнения, обладал необычно высоким, почти юношеским голосом.

В возрасте 11 лет приехал с семьей в Калифорнию. В школе обучался игре на трубе, затем начал выступать в духовых и танцевальных оркестрах. Службу в армии проходил в 3ападном Берлине как трубач военного оркестра (1946-48), после демобилизации продолжил музыкальное образование в колледже Эль-Камино (Лос-Анджелес), где изучал теорию музыки и гармонию. В 1949 получил приглашение в военный оркестр PRESIDIO ARMY BAND, с которым играл в Сан-Франциско до 1952. В этот период познакомился с музыкантами-боперами, участвовал в джем-сешнах.

В начале 1952 сотрудничал с Чарли Паркером и Видо Муссо, в конце того же года в Голливуде примкнул к Джерри Маллигену и вскоре стал знаменитостью как солист его квартета. В дальнейшем выступал преимущественно с собственным комбо (начиная с 1953), членом которого был также пианист Расс Фримен. Совершил несколько европейских турне в 1955-56. Возобновив сотрудничество с Маллигеном, успешно концертировал в составе его секстета в Париже (и как пианист). Аккомпанировал певице Катерине Валенте во время её гастролей в Баден-Бадене.

В 1959-60 находился в Италии, здесь из-за пристрастия к наркотикам перенёс психическое заболевание, был осуждён и в заключении прошёл курс лечения.

«Каждый раз я играю, как будто это последний раз. Уже много лет. Мне немного осталось, и очень важно, чтобы те, с кем я играю — кто бы это ни был, — видели, что я отдаю все, что у меня есть. И я от них жду того же. Мне нравится играть, я люблю играть. Наверное, я для этого и родился».

В 1964 вернулся из Европы в США, снова приобрел широкую известность, принимал участие в различных джазовых фестивалях (в Ньюпорте, Монтерее и др.). В разное время с Бэйкером играли музыканты из Франции, Бельгии, Голландии, ФРГ, Дании (в том числе Нильс-Хеннинг Эрстед-Педерсен, Вольфганг Лаккершмид и др.), среди его американских партнеров — пианисты «Дюк» Джордан, Эл Хэйг, Пол Блей и Дик Туордзик, саксофонисты Стэн Гетц, Ли Кониц, Арт Пеппер и Пол Дезмонд, гитарист Джим Холл, басисты Джимми Бонд, Чарли Хэйден и Рон Картер, барабанщики Питер Литмэн и «Бивер» Харрис.

Источник

Jazz advice

Jazz advice

«>Jazz advice

A Lesson With Chet Baker: But Not For Me

W hat if there were a jazz musician that didn’t rely on scales, licks, or patterns, but instead sought only to play what they’d sing? What would this musician sound like? What kind of playing techniques would they use and how would they approach taking a solo?

This kind of musician is what I hear when I listen to Chet Baker – A player who is not doing math or thinking of chords all the time, but instead mentally singing melodies over the changes, as they effortlessly flow out of his trumpet.

In fact, his solos often sound as if they were a pre-composed alternate melody of the original tune, because how could someone actually play that lyrical and perfect in real-time?

And there’s no short answer to that question…

Years of studying sound, truly hearing chords, understanding jazz language, and developing that singing voice in your head, all-the-while connecting everything to your instrument…this is what it takes, and more…

What sounds so simple, effortless, and melodic is the product of years of hard work and training.

And the problem, or really the challenge, with studying Chet Baker solos is that they don’t necessarily follow the standard formats you’re used to seeing or hearing.

He doesn’t always put everything in neat little ii V packages or play the changes as one might do if they were outlining every single chord change…he doesn’t seem to think that way…

It’s more of answering the question, “How can I craft a melody that moves between chord changes seamlessly, making the chord changes take a backseat in the listener’s ear, and bring my beautiful melodies to the forefront?”

To do this, you can’t simply run up and down the chord changes, using chord arpeggios and such, because that will give the chords too much importance. Instead, you have to focus on the big areas of the tune and learn to hear in a different way.

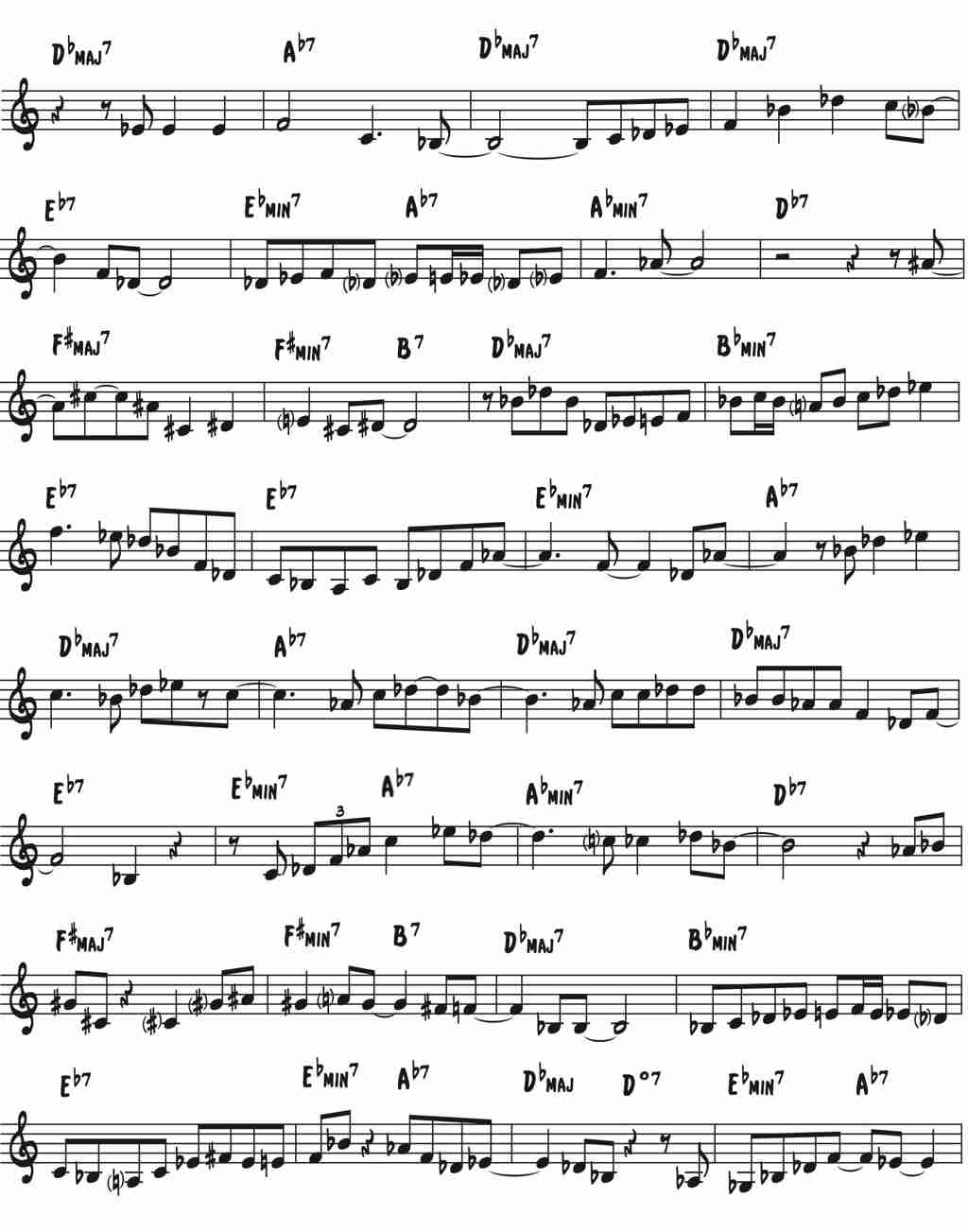

Chet Baker’s Solo: But Not For Me

I know I say this about most solos I transcribe, but when I heard Chet Baker’s solo on But Not For Me, I was astounded…

Never before had I heard anyone play so lyrically over this jazz standard. Of course there are many great recordings of this tune with amazing solos, but this was different.

The clarity of his lines. The forward movement leading from one chord to the next. The rhythmic precision. Everything about Chet Baker’s solo captured my ear.

I had to know more.

Like we say, transcribe things you love…so I got to work (solo at 1:24).

Once I had the solo in front of me, things still weren’t 100% clear – It’s as if a magician had just revealed to me how to do his best trick and my reaction was something along the lines of, “Really?? That’s it??”

This reaction is common when you’re transcribing your heroes because it’s difficult to imagine how the magic you just saw, or in this case heard, is somehow contained in what you now know, but it’s there…hidden in plain sight.

Today we’ll look at some of this magic and put it into usable terms that we can start putting into practice within our own solos so that we might move toward playing more lyrical, melodic, and free, just like the one and only Chet Baker.

New Applications of The Tonic Triad & Chord

One of the primary playing techniques that Chet Baker loves to use in his solos is using material based upon the tonic – both the tonic triad and the tonic 7th chord, which seems pretty basic, right?

But, here’s the catch…

He doesn’t always use them over the tonic chord, but instead applies this tonic thinking to other chords.

And when you take the tonic triad (Db in this case), or the tonic 7th chord (Db major 7), and move it into the context of a different chord, those notes take on new meaning.

No longer does the tonic mean 1-3-5 or 1-3-5-7, but instead it takes on the role of upper extensions, 9-11-13, of a chord.

The first place that he likes to use material based on the tonic triad is over a ii V. So in the key of Db, we’re talking about Eb- Ab7.

Most of the time when we approach a ii V, our thinking will usually go something like this…

We think about the ii chord, play a minor idea, and then think about the V7 chord and play a dominant idea, and there’s nothing wrong with that, in fact Chet does that too, but he doesn’t always do that.

Often, he plays something like in this next line, where he creates a melodic statement based upon the tonic triad.

From my experience, most people don’t think like this, and it never occurs to them that this tonic triad thinking is even an option. So ask yourself…Do I have any simple triad ideas??

If not, go transcribe a a few, and then start using them over ii Vs as an alternative to thinking about each individual chord all the time.

Now another place Chet likes to use the tonic triad is over the ii minor chord. So in the key of Db, that would be Eb-.

This sounds great because it allows you to easily focus on three chord-tones that have a lot of color over the minor chord: 7-9-11

Let me break this down for you at the piano so you can really hear what’s going on…in the left hand I’ll play an Eb minor voicing, and on top of it in the right hand, I’ll play 5-3-1 of the Db major triad.

Listen as I play the triad a few times over the chord and you’ll hear it in action.

The big point to remember here is this: Things like using the tonic triad over the ii minor chord are not just theoretical concepts, they’re sounds. It’s really important to understand this and train your ear to hear the sounds you wish to play.

You can know all the theory in the world, but you have to learn to hear like a jazz musician, acquiring the ability to hear chords, chord-tones, chord voicings and more.

Chet Baker knows what these things SOUND like, and that’s what gives him so much improvisational freedom

And another interesting place he uses tonic based material is over this ii V later in the solo, but in this case, he’s using the Db major 7th chord starting from the 7th of the chord (C) and working his way up the chord tones.

Just like the triad, using the 7th chord allows him to easily get to the upper extensions of the chords, and gives him some interesting ways to move from the upper chord tones of ii to the lower essential chord tones, like the 3rd, of V7.

So there you have a few ways that Chet uses tonic based material…Who knew that the tonic triad or 7th chord could be used in so many ways and so creatively?

And notice that in this particular solo, he’s not using this technique over the tonic chord, the most obvious place where most people would think to use this material. Instead, he’s using tonic based material over ii minor chords and ii Vs.

But for the tonic chord, he’s got a different approach…the relative minor.

New Applications of The Relative Minor

The relative minor is the vi minor of a major key, so in the key of Db major, Bb minor is the relative minor.

This relationship, while overlooked by most jazz players, is fundamental to almost every jazz tune and Chet Baker knows this better than most.

And it’s so important to understand because much of the material that works on one, will work on the other.

So when you’re playing over Db major, in many cases you can think of the relative minor, Bb minor and vice versa. This is a powerful concept as it opens up your perspective on both major and minor chords, while helping you understand the relationship between them.

Now, remember how I said Chet doesn’t use tonic material over the tonic chord in this solo? Well, it’s because the tonic chord is his favorite place to use material from the relative minor.

By capitalizing on this tonic and relative minor relationship, you can easily change your perspective on major chords and play them from a different angle, using pieces of the relative minor scale, as well as triad inversions of the Vi minor chord as Chet does here.

But his use of relative minor material isn’t limited to just the relative major either…

Another place that Chet likes to use material from the relative minor is over the II7 chord, and this makes perfect sense when you think about it…

Pop Quiz: If I asked you to name the minor chord that would pair with the II7 chord to turn it into a ii V, what would you say? In other words, what minor chord leads to the II7 chord?

You probably realized fairly quickly that the chord that the minor chord that leads to Eb7 is Bb minor, but did it ever occur to you how these chords were functioning?

How these chords function creates another important relationship with the relative minor: the ii minor chord that leads to the II7 chord is the Vi, the relative minor.

And just like the tonic and relative minor relationship, Chet Baker is well aware of this relationship, too. Almost every time he encounters the II7 chord, he goes straight to his relative minor language.

This piece of language combines quintessential elements from Bb minor, including the triad, an enclosure using the major 7th, and the chord arpeggio up to the 7th.

All three of these elements reveal how he utilizes material from the relative minor over the II7 chord.

Combining these different elements into a single line creates a strong melodic statement over the II7 chord using language from Bb minor.

And another time he uses relative minor language over this chord happens near the end of the solo.

But here, something else is going on…where does the F# come from and why does it work so well? You may be tempted to think of it as a #9 on the Eb7 chord, but that’s not really how it sounds, or how he’s likely thinking about it.

If you notice, he plays a diminished arpeggio starting on A, moving up to the F# (A-C-Eb-F#). And what this diminished arpeggio actually implies is an F7b9 chord from the 3rd of the chord.

This tactic is central to minor language – using the V7b9 chord of the minor chord. So, he’s first thinking of the relative minor chord, Bb minor, and then uses the V7b9 chord of that chord on top of it.

While this idea seems complex, it’s all a part of minor language that you’ll quickly hear and see when you start transcribing, and with it, Chet opens up even more possibilities for how he applies the relative minor over the II7 chord.

Now, beyond how Chet thinks harmonically, a lot of his magic comes from his keen ability to highlight what’s important at any given moment in the most eloquent of ways…

Emphasizing Small Changes

A lot of times when we’re playing over changes we automatically think that we need to outline every single chord, and that our job is to communicate every detail of every chord to the listener…but that’s not the case…

Sometimes with the smallest amount of information, the most is conveyed.

Chet Baker loves to emphasize a little tiny change from one chord to the next that encapsulates the essence of the transition from one chord to the next.

Be it a major third changing to a minor 3rd, or major 7th that’s shifting to minor, he likes to highlight these exact moments for the listener within his improvised melodies.

By using this technique, he doesn’t need to play a whole line, pattern, scale or arpeggio to give the listener something to grab on to. In fact, by removing all this typical clutter and emphasizing the essential difference between two chords, his improvised melodies have a continuity rarely heard by other musicians…

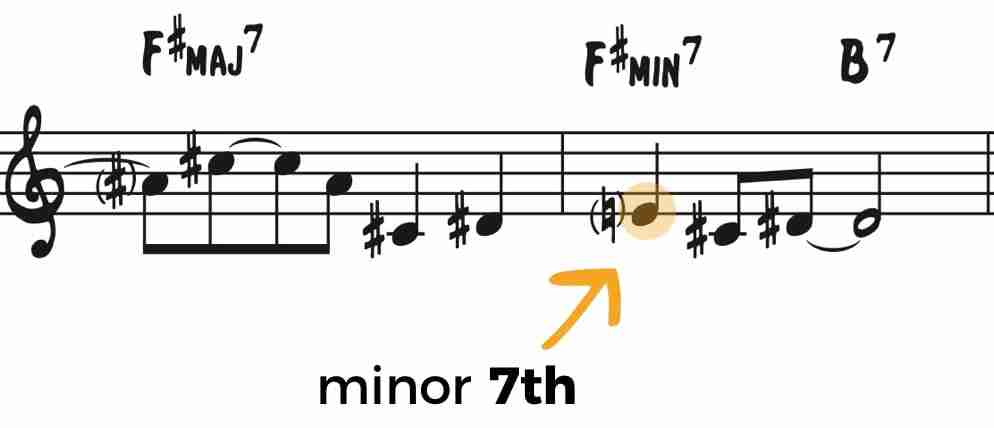

Check out how he communicates the transition from F# major to F# minor by emphasizing the minor 7th over F# minor.

When he arrives at F# minor, the flow of his line from F# major continues – he doesn’t stop and then start a brand new idea over F# minor. He plays one continuous line from major to minor by simply highlighting the move from the major 7th to the minor 7th.

And the second time he reaches this point in the tune, he uses the exact same improvisational technique, but instead of emphasizing the 7th, he focuses on the shift from major to minor 3rd.

He achieves the same continuity he did in the last example by emphasizing an essential move from one chord to another and highlighting the crucial change.

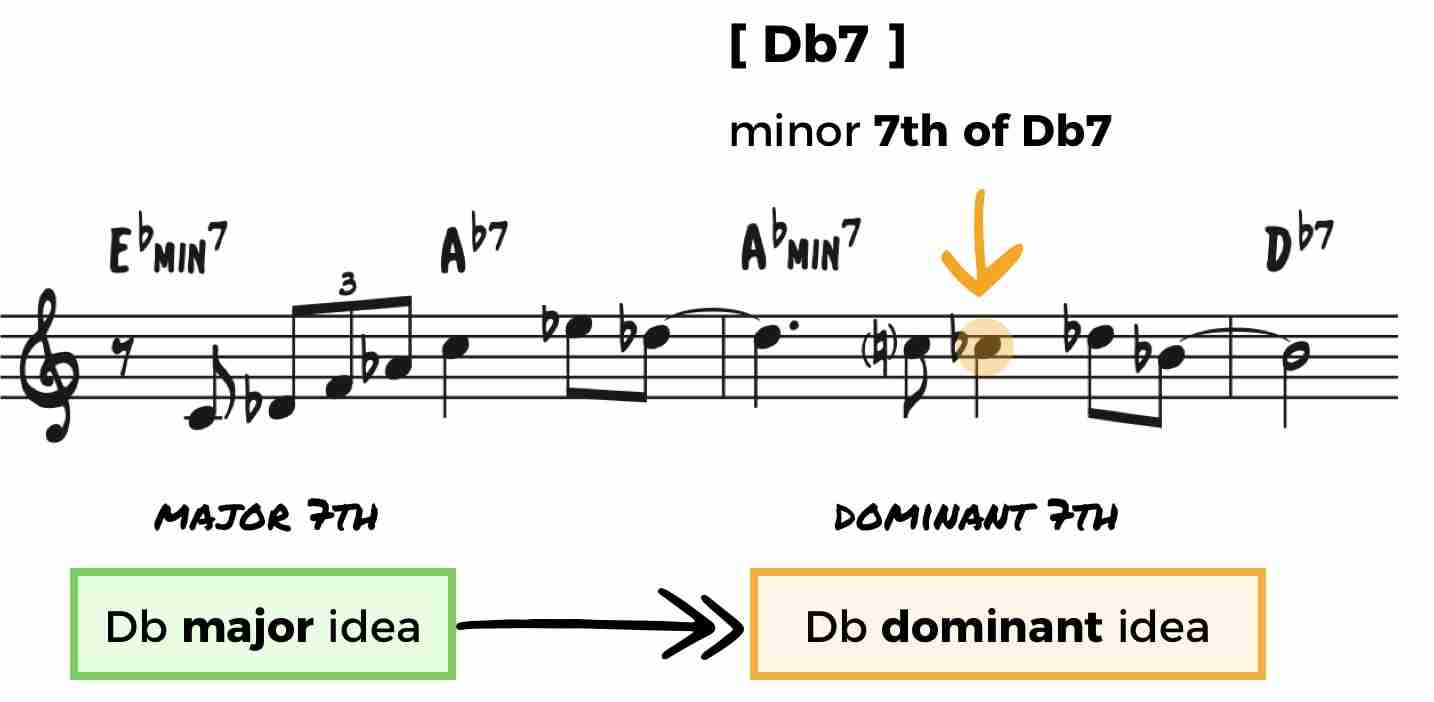

And another interesting place where Chet uses this approach is right before the ii V of IV where we saw him arpeggiate a Db major 7 chord.

He emphasizes the minor 3rd of the Ab minor chord, a chord-tone not present in the ii V leading up to it. But, perhaps a more clear way to look at why this line is so melodically strong comes from understanding that the idea he plays over Ab minor comes from Db dominant language.

And, from before, that the line over the ii V chord comes from a Db major 7 arpeggio. See what we’re getting at?

If you’re moving from Db major to Db dominant, what’s the little change to emphasize? The major 7th moving to the dominant 7th.

Obviously I can’t tell you if Chet Baker was thinking this exact way, however, I can tell you that structurally, this underlying idea helps explain why his improvised melody here is so strong, and how it clearly communicates the changes by focusing on the essence of each chord.

Learning to spot what’s different between one chord and the next, as well as what’s common, will help you find these key places to bring these moments to life.

Remember, sometimes you can say a lot more with less if you focus on what’s most important.

Chet Baker Takeaways

So today you learned the importance of having tonic based material and that it’s not limited to using over the tonic chord, but can actually be applied to many different spots in a jazz standard, the various ways that Chet Baker does over and over.

Having an arsenal of tonic based material, including triadic ideas and 7th chords, while knowing when and where to use these tools will open up how you think about the tonic.

Next, make sure you realize why the relationship between the tonic and the relative minor is not to be underestimated – that it’s integral to playing jazz and understanding tunes. With it, you can learn a lot about how to approach major chords in a new way, and how to use minor based language throughout your solos.

And a huge takeaway from Chet Baker is this: you don’t need to outline every single chord. Much of the time, you can communicate more with less by emphasizing a small change from one chord to the next. Learn to spot these moments in the changes and use this tactic in your own lines.

With these 3 tools from Chet from his solo on But Not For Me, you should now have a little more insight into how he plays, thinks, and constructs melodic statements.

And today I want to leave you with one more thing…right now the world is going through some difficult and trying times. Most of us are isolated and wondering how all of this will play out.

While I don’t have any answers, I can tell you that working with Chet’s solo this week has helped me stay motivated, creative, and happy, because every time I listen to him play I’m in a better mental space.

You can do this too. Find solace in music. Use the quiet to connect to the music like never before. And be inspired by the greatness that can be heard on the recordings of your heroes. Remember, you always have music, and jazz will always be there for you!! Stay happy, keep improving and practicing, and we’ll get through this together.

Источник